The Australian PCEHR or My Health Record: The Journey Around a Large-Scale Nationwide Digital Health Solution

This case study attempts to document key events and milestones in the development of Australia’s nationwide digital health solution the My Health Record (formerly known as the PCEHR). This is done by presenting an overview of the Australian healthcare system and in particular highlighting unique features about this system into which the My Health Record was implemented. This journey has only just begun, and in the next decades, it is expected that the My Health Record will change and evolve further; hence, the case study concludes with questions for the reader to consider rather than provide final statements. Ultimately, the success of such a solution can only be judged in the fullness of time; however, we note that this was a massive undertaking that has had far-reaching implications for healthcare delivery throughout Australia and impacts all stakeholders including patients, providers, payers, the regulator and healthcare organizations.

This case study has been written to capture the developments of a large-scale health technology journey to facilitate discussions, teaching, and learning only. It is not designed to identify good or bad management practices or make any comments about any of the organizations or individuals involved.

This case study is forthcoming as a chapter in a book publication by Springer, New York Eds Wickramasinghe, N and Bodendorf, F. 2019 Delivering superior health and wellness management with IoT and analytics and may only be used for educational purposes with the written permission of the authors.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save

Springer+ Basic

€32.70 /Month

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Buy Now

Price includes VAT (France)

eBook EUR 93.08 Price includes VAT (France)

Softcover Book EUR 116.04 Price includes VAT (France)

Hardcover Book EUR 158.24 Price includes VAT (France)

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Recent US Experience with Health ICT

Chapter © 2014

Opening the Door to Digital Health

Chapter © 2023

Current Status, Challenges, and Outlook of E-Health Record Systems in Australia

Chapter © 2014

References

- ABS. (2013). Australian demographic statistics, Mar 2013. Retrieved July 26, 2011, from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3101.0

- AIHW. (2012). Australia’s health 2012: The Thirteenth Biennial Health Report of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. AIHW. Google Scholar

- AIHW. (2013). Health expenditure Australia 2011–12 (AIHW). Retrieved from http://www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=60129544658

- Anonymous. (2010). Our current health care system is simple: Don’t get sick, PNHP. Retrieved Aug 2018 at http://www.pnhp.org/single_payer_resources/health_care_systems_four_basic_models.php

- Armstrong, B. K., Gillespie, J. A., Leeder, S. R., Rubin, G. L., & Russell, L. M. (2007). Challenges in health and health care for Australia. The Medical Journal of Australia, 187(9), 485–489. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Australian Digital Health Agency. (2018). What is My Health Record. Accessed Aug 2018 form https://www.myhealthrecord.gov.au/for-you-your-family/what-is-my-health-record

- Bartlett, C., Boehncke, K., & Haikerwal, M. (2008). E-health: Enabler for Australia’s health reform (p. 66). National Health & Hospitals Reform Commission. Retrieved from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/nhhrc/publishing.nsf/Content/16F7A93D8F578DB4CA2574D7001830E9/$File/E-Health%20-%20Enabler%20for%20Australia%27s%20Health%20Reform,%20Booz%20&%20Company, %20November%202008.pdf

- Behan, P. (2007). Solving the health care problem: How other nations succeeded and why the United States has not. New York: SUNY Press. Google Scholar

- Berwick, D. M. (2003). Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.15.1969.

- Currell, R., Urquhart, C., Wainwright, P., & Lewis, R. (2000). Telemedicine versus face to face patient care: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. In The Cochrane Collaboration & R. Currell (Eds.), Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Retrieved from http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab002098.html. Google Scholar

- Deloitte. (2015a). IT project risk an abiding CIO challenge. CIO Journal. Retrieved from https://deloitte.wsj.com/cio/2015/05/14/it-project-risk-an-abiding-cio-challenge/

- Deloitte. (2015b). Enterprise risk management. A ‘risk-intelligent’ approach. Deloitte Risk Advisory 2015. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/audit/deloitte-uk-erm-a-risk-intelligent-approach.pdf

- DoHA. (2010). Building a 21st century – Primary health care system – Australia’s First National Primary Health Care Strategy. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Retrieved from http://www.yourhealth.gov.au/internet/yourhealth/publishing.nsf/Content/Building-a-21st-Century-Primary-Health-Care-System-TOC

- DoHA & NEHTA. (2011). Concept of operations: Relating to the introduction of a personally controlled electronic health record system (Article). p. 159. Google Scholar

- Duckett, S., & Willcox, S. (2011). The Australian health care system. (4th revised ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. Google Scholar

- Dwyer, J., & Eagar, K. (2008). Options for reform of commonwealth and state governance responsibilities for the Australian health system. A Paper Commissioned by the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. Google Scholar

- Foo, F. (2012). Canberra admits PCEHR delays COMPLETE ROLLOUT MAY TAKE A FEW MORE MONTHS. Canberra, ACT, Australia: The Australian. Google Scholar

- Gartner. (2006). Defining IT governance: Roles and relationships. New York: Gartner, Inc. Google Scholar

- Gartner. (2014). Six required elements of effective risk management. New York: Gartner, Inc. Google Scholar

- Gartner. (2017). ITScore overview for program and portfolio management. New York: Gartner, Inc. Google Scholar

- Gartner. (2018). Hype cycle for risk management, 2018. New York: Gartner, Inc. Google Scholar

- Hall, J. (2010). Australian health care reform: Giant leap or small step? Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 15(4), 193–194. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2010.010090. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hartman, M., Martin, A., McDonnell, P., & Catlin, A. (2009). National health spending in 2007: Slower drug spending contributes to lowest rate of overall growth since 1998. Health Affairs, 28(1), 246. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Heslop, L. (2010). Patient and health care delivery systems in the US. Canada and Australia: A critical ethnographic analysis. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing. Google Scholar

- ITGI. (2003). Board briefing on IT governance (2nd ed.). New York: IT Governance Institute. Google Scholar

- ISO/IEC. (2015). Information technology – Governance of IT for the organization. ISO/IEC, 38500, 2015. Google Scholar

- ISO. (2018). ISO 31000:2018 – Risk management. New York: International Organization for Standardization. Google Scholar

- Jones, T. (2011). Developing an E-Health strategy: A commonwealth workbook of methodologies, Content and models. New York: Commonwealth Secretariat Google Scholar

- Lehnbom, E. C., McLachlan, A., & Jo-anne, E. B. (2012). A qualitative study of Australians’ opinions about personally controlled electronic health records. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 178, 105–110. PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Liaw, S.-T., & Hannan, T. (2010). Can we trust the PCEHR not to leak? Australian Family Physician, 39, 809–810. PubMedGoogle Scholar

- Lindros, K. (2017). What is IT governance? A formal way to align IT & business strategy. Retrieved from https://www.cio.com/article/2438931/governance/governanceit-governance-definition-and-solutions.html

- McDonald, K. (2012). Use it or lose it—PCEHR for PIP’, PULSE+IT. https://www.pulseitmagazine.com.au/news/australian-ehealth/983-use-it-or-lose-it-pcehr-for-pip

- Muhammad, I., Teoh, S. Y., & Wickramasinghe, N. (2012). Why using Actor Network Theory (ANT) can help to understand the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record (PCEHR) in Australia. International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation (IJANTTI), 4(2), 44–60. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Muhammad, I., & Wickramasinghe, N. (2014). How an Actor Network Theory (ANT) analysis can help us to understand the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record (PCEHR) in Australia. In Technological advancements and the impact of actor-network theory (pp. 15–34). Heidelberg: IGI Global. Google Scholar

- Naismith, P. (2012). eHorizons: The PCEHR future is here. AJP: The Australian Journal of Pharmacy, 93(1106), 62. Google Scholar

- NEHTA. (2013). NEHTA’s Annual Report 2012–13. Google Scholar

- NEHTA. (2014). Secure Message Delivery (SMD) – NEHTA. Google Scholar

- NHHRC. (2009a). A Healthier future for all Australians: National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission – Final Report June 2009. New York: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Google Scholar

- NHHRC. (2009b). Future for all Australians: National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission-Final Report June. New York: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Google Scholar

- OECD. (2013). Health at a glance 2013: OECD indicators. New York: OECD. Google Scholar

- OECD. (2017). Health at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. New York: OECD. Google Scholar

- Productivity Commission. (2005). Impacts of advances in medical technology in Australia. New York: Productivity Commission. Google Scholar

- Rhyne, L. (2008). An explorative case study of the transition to the electronic clinical record in the south Australian acute healthcare context: A diffusion of innovation perspective. New York: Citeseer. Google Scholar

- Shields, A. E., Shin, P., Leu, M. G., Levy, D. E., Betancourt, R. M., Hawkins, D., & Proser, M. (2007). Adoption of health information technology in community health centers: Results of a National Survey. Health Affairs, 26(5), 1373–1383. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1373. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Showell, C. M. (2011). Citizens, patients and policy: A challenge for Australia’s national electronic health record. Health Information Management Journal, 40(2), 39–43. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Smartsheet. (2018). Demystifying the various project management frameworks and methodologies. Retrieved from https://www.smartsheet.com/demystifying-various-project-management-frameworks-and-methodologies

- Spriggs, M., Arnold, M. V., Pearce, C. M., & Fry, C. (2012). Ethical questions must be considered for electronic health records. Journal of Medical Ethics, 38(9), 535–539. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2011-100413. ArticlePubMedGoogle Scholar

- Stead, D. (2010). Improving project success – Managing projects in complex environments and project recovery. Retrieved from https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/complex-environments-resolving-challenges-success-6923

- Wall, A. (2002). Health Care Systems in Liberal Democracies. New York: Taylor & Francis Google Scholar

- Westbrook, J. I., Braithwaite, J., Gibson, K., Paoloni, R., Callen, J., Georgiou, A., & Robertson, L. (2009). Use of information and communication technologies to support effective work practice innovation in the health sector: A multi-site study. BMC Health Services Book, 9(1), 201. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-9-201. ArticleGoogle Scholar

- WHO. (2000). The world health report 2000: Health systems: improving performance. World Health Organization. Google Scholar

- WHO. (2006). The world health report 2006: Working together for health. World Health Organization. Google Scholar

- Wickramasinghe, N., & Schaffer, J. (2010). Realizing value driven e-health solutions. Washington, DC: Report for IBM. Google Scholar

- Willis, E., Reynolds, L., & Helen, K. (2009). Understanding the Australian health care system. Australia: Elsevier. Google Scholar

- Wise, G. R., & Bankowitz, R. (2009). Keys to engaging clinicians in clinical IT. Healthcare Financial Management: Journal of the Healthcare Financial Management Association, 63(3), 66–72. Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge with thanks all the organizations and individuals who assisted us with information to help us compile this case study. In particular, we acknowledge Dr. Imran Muhammad for his inputs on early drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Epworth HealthCare, Richmond, VIC, Australia Nilmini Wickramasinghe

- Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC, Australia Nilmini Wickramasinghe

- Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC, Australia John Zelcer

- Nilmini Wickramasinghe

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

- Epworth HealthCare, Richmond, VIC, Australia, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC, Australia Nilmini Wickramasinghe

- Friedrich-Alexander-University, Erlangen-Nuremberg, Erlangen, Germany Freimut Bodendorf

Appendices

Appendix 1: Comparative Performance of the Australian Healthcare System

Compared to many other developed nations, the Australian healthcare system delivers above average outcomes (DoHA 2010), and the Australian population is ranked one of the best in terms of health status, with an average life expectancy at birth of 81.4 years, and there has been a significant decline in infant and youth mortality rates over the period of 1988 to 2007 (AIHW 2012).

Australia’s population is healthier than the OECD average, considering life expectancy and other general measures of health status (OECD 2013, 2017). Smoking consumption is also low, as is exposure to air pollution. But obesity rates are the fifth highest in the OECD (ibid). Further, despite universal health coverage, a relatively high share of the population reported skipping consultations due to cost (ibid). Quality of care indicators also show mixed results (ibid). The figure below shows how Australia compares across these and other core indicators from Health at a Glance (ibid).

This comparison is shown in a Table 2 (from OECD 2013, 2017).

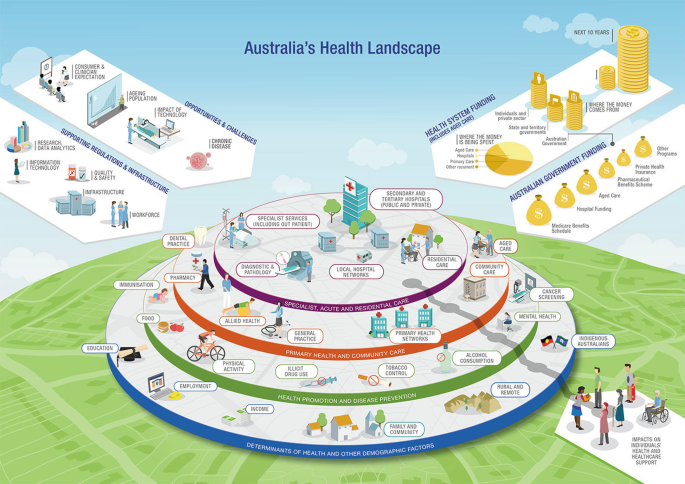

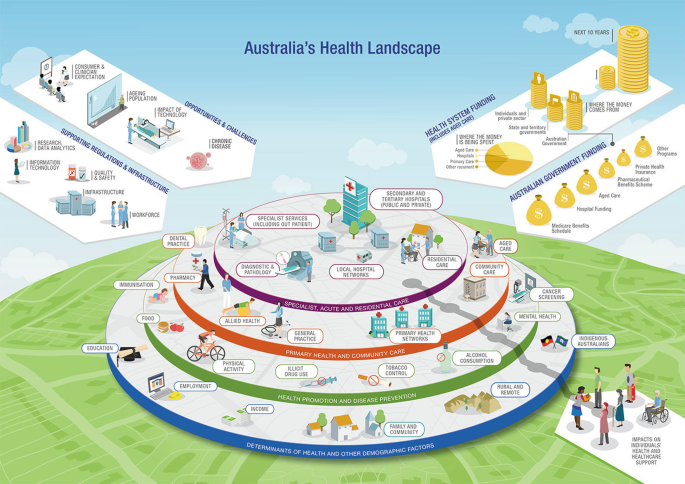

Factors that contribute to the health landscape (ibid):

- Impacts on individuals’ health and healthcare support

- Opportunities and challenges, including consumer and clinician expectation, ageing population, impact of technology and chronic disease

- Supporting regulations and infrastructure, including research and data analytics, information technology, quality and safety, infrastructure and workforce

- Health system funding of $2.3 trillion over the next 10 years. The funding in 2014–2015 was $182 billion including aged care. 11.9% was spent on aged care, 36.1% on hospitals, 32.7% on primary care and 19.3% on other recurrent costs. $58 billion came from individuals and the private sector, $43 billion from state and territory governments and $81 billion from the Australian government. The Australian government funding was for (from largest to smallest):

- Medicare Benefits Schedule

- Hospital funding

- Aged care

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme

- Private health insurance

- Consolidated funds

- Research

Public hospitals are managed and operated under the ownership of state and territory governments which provide free service at the point of delivery for all Australian citizens. State and territory governments are also responsible for the delivery of community health, aged care, mental health, patient transport and dental services for mostly free of cost to Australian consumers.

The Commonwealth government is responsible for healthcare policy development, healthcare service regulation and healthcare funding through Australian Health Care Agreements (AHCA) to state and territory governments as well as providing healthcare service rebates to patients through Medicare Australia, a universal health insurance system and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, as well as regulating the private health insurance industry (Duckett and Willcox 2011; Willis et al. 2009).

Medicare provides universal access to subsidized care and pharmaceutical benefits. Medicare is partially funded by an income tax surcharge known as the Medicare levy (currently 1.5% of the taxable income or 2.5% for those who are high income earners and do not have private health insurance) and the balance is provided by government from general revenue (AIHW 2012). The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has estimated that the total Australian health expenditure is $140.24 billion in 2011–2012 (AIHW 2013). This represents 9.5% of GDP. Another important component of Australian healthcare system financing is private health insurance (ibid). The Australian government encourages citizens to enrol for private insurance by giving them tax benefits for private health insurance premiums paid (ibid).

The flow of money around the healthcare system of Australia is a complex phenomenon and can be controlled by the institutional frameworks in place at both government and non-government levels. The government sector in this respect is comprised of federal, state and territory governments, and in some jurisdictions, local governments are involved (ibid). The non-government sector includes individuals, private health insurers, and other different non-government funding sources (ibid). The other non-government sources include worker’s compensation, compulsory third-party motor vehicle insurers, donations for health-related research and miscellaneous non-patient revenue sources for hospitals (ibid). The complexity of these funding arrangements and interaction between different levels of service providers and consumers in healthcare service delivery is explained here (ibid).

The funding model for healthcare services and delivery in Australia has perceived political polarization, with governments being critical in determining nationwide healthcare policy (Behan 2007). This leads to administrative duplications and lack of coordination at national level resulting in slow reactive and inefficient health policy (Wall 2002).

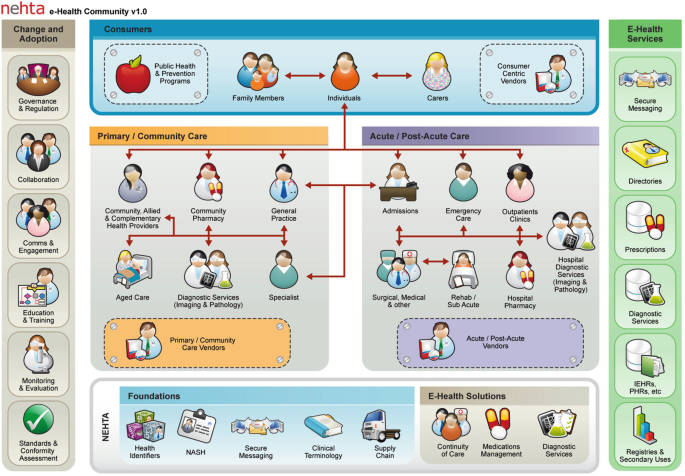

Appendix 3: System Architecture of the My Health Record

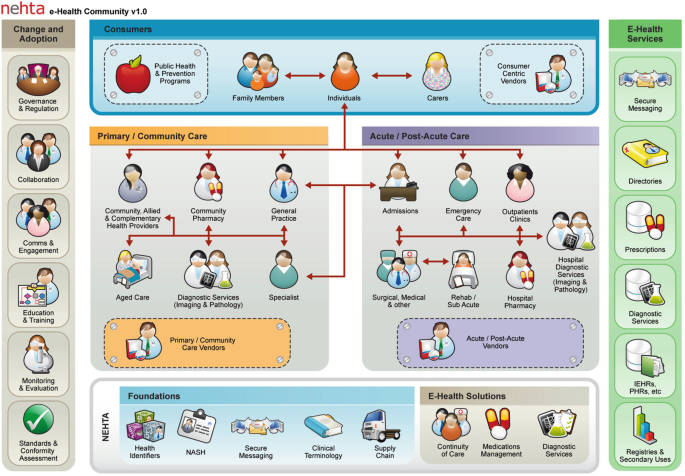

The My Health Record system (previously PCEHR) is situated in an e-Health ecosystem that has been designed to serve a number of communities:

- Consumers – including the individuals themselves, their family members and their carers. This also extends to working with organizations that promote public health and prevention programmes as well as those organizations that support self-managed care.

- Primary/community-based care – organizations and their staff, including, but not limited to, general practices, community pharmacies, allied and complementary healthcare providers, diagnostic imaging and pathology providers, specialists and aged care services.

- Acute/post-acute care – organizations and services, including, but not limited to, admissions, emergency care, outpatient care, surgical and medical care, rehab and subacute care units, hospital pharmacies and hospital diagnostic imaging and pathology providers. [Does this include Medibank Private, MBF, Medicare].

- Vendors – who provide products and services to support primary/community-based care, acute/post-acute care and consumers.

- e-Health services – operated either by public or private sector service providers that deliver online e-Health services, such as secure messaging, directories, prescription services, diagnostic services, registries and other secondary use services.

The e-Health community is also supported by a range of foundations (or national infrastructure) and standards for e-Health solutions (Fig. 6).

Building on a series of stages of development, the PCEHR system provides a number of core services that allow authorized users to search for an individual’s PCEHR, clinical documents, view clinical documents and access reports.

A key feature of the PCEHR System is its ability to provide a series of views leveraging different clinical documents in an individual’s PCEHR. These views allow users of the system to easily see a consolidated overview of an individual’s allergies/adverse reactions, medicines, medical history, immunizations, directives and recent healthcare events from different information sources.

In the context of a national approach to e-Health, local systems at the point of care or in the home will be able to access a range of services, including:

- National infrastructure services, including, but not limited to, the Healthcare Identifier Service, National Authentication Service for Health, etc.

- Public- or private-operated online services, including, but not limited to, pathology services, radiology services, prescription exchange services, etc.

The interfaces for these services are based on national and international standards and other agreed specifications (Fig. 7).